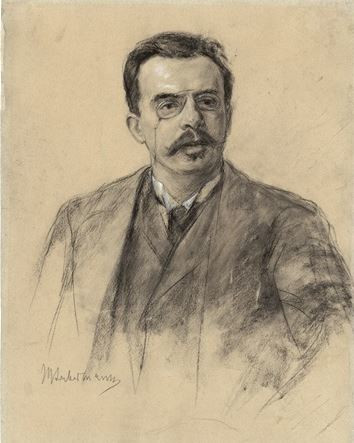

Fritz and Annarella Gurlitt

Portrait of Fritz Gurlitt drawn by Max Liebermann.

The image is in the public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Annarella Gurlitt painted by E. Hildebrand.

Photo taken from a large-format negative. The painting is in the public domain.

Note: The Marburg Photo Archive also has a similar photograph.

Source: Private Archive. © Alexandra Cedrino

My great-grandparents' marriage ended in an lunatic asylum of all places. Not exactly glamorous - even though it was a private sanatorium for wealthy patients. And although everything was furnished in the most pleasant way - extensive parks were perfect for a stroll, there was a concert hall, a billiard parlour, a terrace, a flower garden and vine arbours - it was still an asylum with security beds and barred windows. The wealthy patient who was accommodated here - in Güntz's sanatorium and nursing home - was called Fritz Gurlitt and was an art dealer. The diagnosis: progressive paralysis caused by untreated syphilis. The symptoms: personality changes, a tendency to delusions of grandeur, hallucinations, speech disorders, motor restlessness and epilepsy. Today, syphilis can be treated with antibiotics - in 1892 this was not yet possible. The course of the disease can drag on for years. Not so with Fritz. In March 1892, he was admitted to the Maison de Santé in Berlin-Schöneberg, in September to Güntz'sche Heilanstalt - and in February 1893, a few days before his son Wolfgang's fifth birthday, he was already dead.

Yet everything had started so well! In 1881, he married Annarella Imhof, the beautiful daughter of the Swiss sculptor Heinrich Imhof in Rome, where she had grown up. Their daughter Angelina was born in 1882, Margarete in 1885 and their first son Wolfgang Ludwig Heinrich Karl on 15 February 1888, Ash Wednesday, at 11.45 pm. In 1890, the youngest, Manfred, completed the rapidly growing family. Fritz loved his dark-haired, spirited wife. When they were separated by business trips, they signed their letters “lots, lots of love”. They liked to keep to themselves and did not seek close contact with the family, which later led to Annarella being accused of “isolating” Fritz.

Fritz was very successful in business. He particularly appreciated the new German painting, the realism and individualism of Max Liebermann and Lesser Ury. A renewal that was orientated towards French painting without imitating it was important to him. However, his vehement commitment was met with incomprehension by many of his contemporaries. Against all odds, he nevertheless succeeded in establishing his art salon as one of Berlin's leading art dealerships.

His success boosted his self-confidence. The world exhibition in Chicago in 1893 was the big goal.

To show that he could hold his own on the international stage, he decided to take part in the “German Exhibition” in London in 1891. He travelled to England with his wife and children, put them up with his brother Otto, who had been living in England as a banker for years, and threw himself into his work. As “Director for the Fine Art Section”, he was responsible for hanging the paintings. He put in a great deal of effort, had “worked terribly hard and […] achieved a moral success […]” (1).

But just a few months later, the symptoms of untreated syphilis put a spanner in the works. Fritz’s health deteriorated rapidly. His brother Cornelius temporarily took over the business. Arrangements were made for the worst-case scenario. But the support was for Fritz and the children, not his wife. The Gurlitt family could not cope with the self-confident Annarella. In one of his letters, her brother-in-law Cornelius described her as a primitive creature(2) with a bird’s brain(3).

On 8 February 1893 - at the age of just 39 - Fritz died as a result of his illness.

What was to become of the gallery and his family? It would certainly have been easier to fulfil the Gurlitt family’s wish to sell the art gallery and withdraw from the public eye with the children until a suitable marriage candidate appeared on the scene. But Annarella was anything but prepared to submit to the unloved family. She wanted to be independent, break away from the family and realise her own ideas. But to do this, she needed a man. Even before Fritz’s death, she had found someone who wanted to marry her. It was to be the partner Willy Waldecker, who had been taken into the company by Fritz himself. To the Gurlitts, it all looked like treacherous betrayal and adultery. She was a whore, her late husband’s brother Cornelius insulted her on the eve of the funeral and threw her out.

The widow, who was only 37, married in the same year. Her daughters Angelina and Margarete were eleven and eight years old, Wolfgang was just five and Manfred only three. From then on, their mother had little time for them as she had to look after the business together with her new husband.

A rift went through the Gurlitt family that could never be completely healed. The Gurlitts were hostile towards Annarella and her second husband. From then on, contact between the two branches of the family remained cool and sporadic.

Annarella’s son Wolfgang joined the business in 1907 and took on responsibility from the outset. Although he “only” worked as an employee of the Fritz Gurlitt art salon for five years, he brought a breath of fresh air to the ailing gallery. And that was sorely needed. In the years since his father’s death, the German art (trade) landscape had changed fundamentally. The “Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt” was no longer the only one championing progressive and avant-garde art. The competition had grown considerably. In 1912, Wolfgang Gurlitt finally took over the business.

How he made the gallery successful again is another story …

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed it, I would be more than happy if you would support my work by subscribing to my blogposts, liking them, sharing them with others, writing a comment or buying my books.

(1) Archiv Cornelius Gurlitt, TU Dresden, letter dated 04.06.1891 from Fritz Gurlitt to Wilhelm (Memo) Gurlitt

(2) Archiv Cornelius Gurlitt, TU Dresden, letter dated 05.02.1893 from Cornelius Gurlitt to Wilhelm (Memo) Gurlitt

(3) Archiv Cornelius Gurlitt, TU Dresden, letter dated Dezember 1887 from Cornelius Gurlitt to Wilhelm (Memo) Gurlitt

Alexandra Cedrino, historical novels, German author, contemporary literature, literature and art, art history, German history, art dealer family, art trade, erotic art, writer, Die Galerie am Potsdamer Platz, The Gallery at Potsdamer Platz, Gallery Trilogy, Zeitenwende am Potsdamer Platz, Shadows over Potsdamer Platz, Wiedersehen am Potsdamer Platz, Return to Potsdamer Platz, The Passion of Searching and Finding, The Journey of Pictures, historical book series, historical crime novels, historical family stories, Italian translation, Berlin, Potsdamer Platz, 1930s Berlin, National Socialism, Nazi art theft, Salzkammergut, Bad Aussee, Alt-Aussee, Austria, post-war period, Central Art Collecting Point, art scene, looted art, art politics, German art history, post-war Berlin, historical villas Berlin, art collections, Wolfgang Gurlitt, Gurlitt family, art collector, publisher, historical figures, family history, artistic networks, inspiration from family history, exhibition catalog, Hirmer Verlag, Lentos Art Museum Linz, essays and articles, book publications, historical essays, reviews, literary criticism, interviews, literary awards, book fairs, HarperCollins Germany, Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024, Führermuseum, art exhibitions, readings, literary events, book presentations, art history lectures, historical conferences, historical narratives, literary suspense, cultural diversity, artistic freedom, erotic private prints, publishing, art and culture, cultural heritage, art market, Nazi-era art, art historical research, cultural political topics, Wolfgang Gurlitt biography, Wolfgang Gurlitt art dealer, Wolfgang Gurlitt art collector, Wolfgang Gurlitt publisher, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the Nazi era, Wolfgang Gurlitt exhibition, Wolfgang Gurlitt family history, Wolfgang Gurlitt art, Wolfgang Gurlitt estate, Wolfgang Gurlitt and Hildebrand Gurlitt, Wolfgang Gurlitt and National Socialism, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the art trade, Wolfgang Gurlitt art relocation, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the Salzkammergut art depots, photographer, art dealer, German-Irish, Nazis, family, love, art collection.