Rescued Modernism

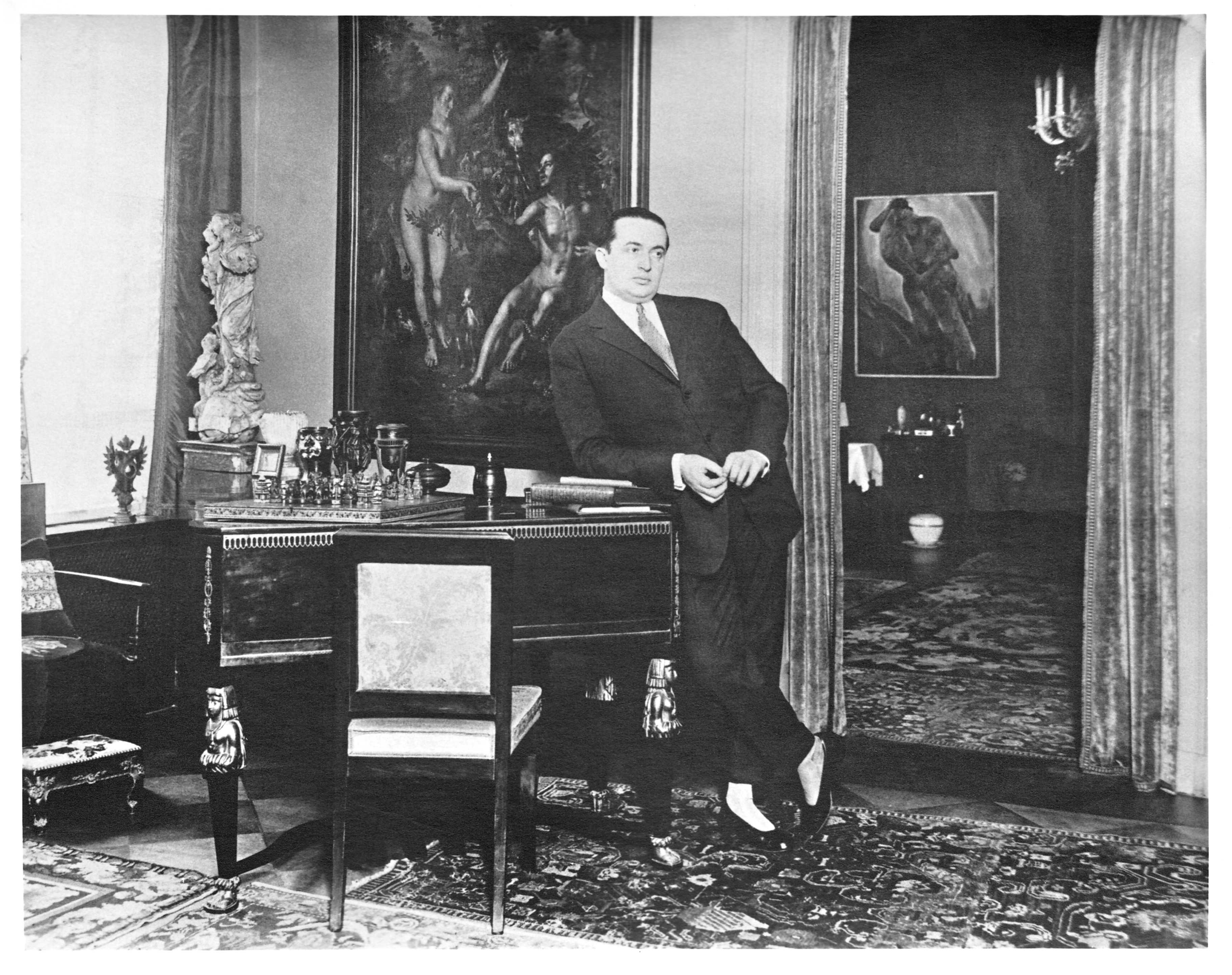

Wolfgang Gurlitt in his apartment on Potsdamer Strasse, Berlin, around 1926.

Source: Private Archive. © Alexandra Cedrino

No matter where I go in Berlin, which book or catalogue I open, I always come across my family. Or rather: my great-grandfather Fritz (1854 - 1893) or my grandfather Wolfgang Gurlitt (1888 - 1965). Both were respected art dealers in their day.

My great-grandfather founded the Fritz Gurlitt Art Salon. His gallery was appreciated by open-minded critics because it was a clear modernist accent in a rather provincial Berlin.

“The third gallery,” as a contemporary (1) described it in a book published in 1887, “is located in Behrenstraße, the first parallel street to the Linden. It is the only art shop in the whole of Berlin. Mr Gurlitt, a still young, very intelligent man who knows everything that happens in art beyond the borders, is in charge here. The shop is cramped, but from time to time there are good exhibitions, sometimes of one master, sometimes of several. Memorable boldness: an exhibition of French Impressionists was on show there. If Berlin becomes a little art savvy, it will be thanks to Mr Gurlitt.”

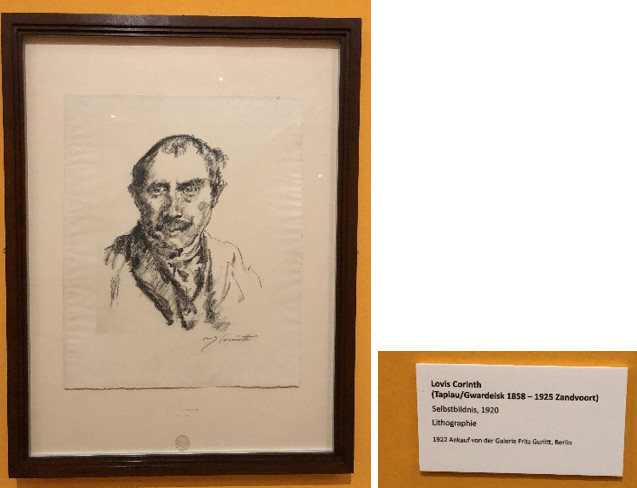

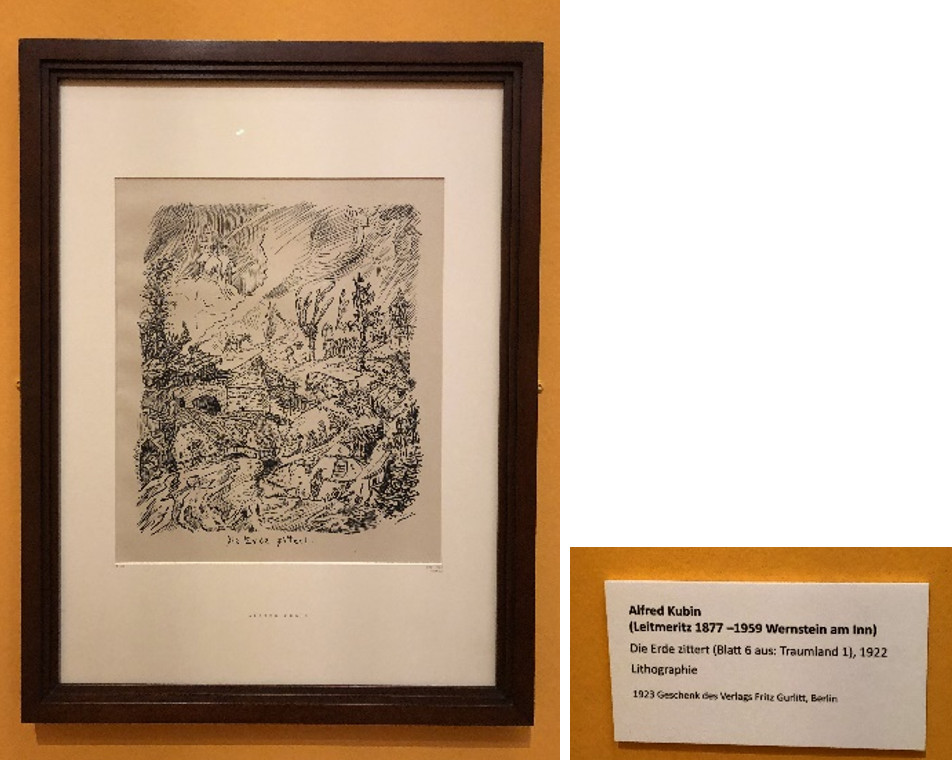

Fritz's son Wolfgang, who joined the company in 1907 at the age of 19 and took over the management in 1914, wanted to maintain and continue the programme introduced by his father. Time and again, he exhibited works by artists such as Leibl, Thoma, Böcklin, Uhde and other recognised greats of the 19th century. But his intuition told him that he had to look ahead, that he had to look after the young artists, even or especially when they were not yet known and were often reviled. Wolfgang had a keen sense for developments and trends and succeeded in winning over some of the most famous painters and graphic artists. Names such as Alfred Kubin, Oskar Kokoschka, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Curt Herrmann, Ernst Seewald, Jeanne Mammen, Rudolf Belling and Richard Janthour will always be associated with him.

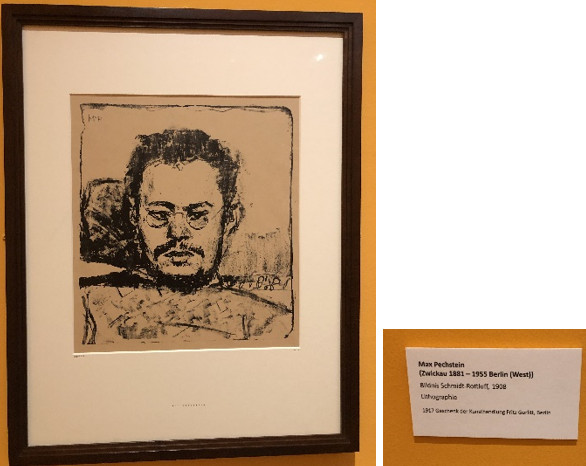

Max Pechstein was a particularly important artist for Wolfgang Gurlitt. Shortly before the Brücke Group broke up in 1913, he succeeded in organising the group's only closed exhibition in Berlin in 1912 - and thus laid the foundation for several years of fruitful collaboration with the most sought-after member of the association, Max Pechstein.

In 1914, Wolfgang had already founded the 'Kunstverlag Gurlitt' as a second branch of his business. More and more collectors were interested in prints, which were considerably cheaper and, above all, easier to store than paintings.

After the war, interest in this art form did not wane - on the contrary. Other art dealers and publishers also recognised the advantages of this shift in interest. A painting could only be sold once - prints, on the other hand, appeared in much larger editions!

In addition, there was a shortage of food after the war, but not of good paper and cheap labour, which significantly improved the profit margin.

In the years leading up to the Great Depression of 1929/30, a myriad of large and small publishers flooded the market.

Many of Wolfgang's 'house artists' such as Corinth, Kokoschka, Kubin and Pechstein worked with graphic art. What could be more obvious than to publish these - together with texts, essays and essays by renowned art historians, critics and writers - in larger editions?

The publishing programme, which Wolfgang designed and supervised together with his production manager Paul Eipper from 1920 to 1924, was ambitious. Art books, individual prints, portfolios, yearbooks, illustrated books and painting books were published in a wide variety of formats and designs, with precious bindings and hand-signed original prints on Japanese or laid paper. In addition to these splendid editions, cheaper versions were also published in more modest editions with unsigned prints.

So when I visited the exhibition “Rescued Modernism - Masterpieces from Kirchner to Picasso” at the Kupferstichkabinett a few days ago, it was only logical that I also came across some of the works that my grandfather had donated to the Kupferstichkabinett on behalf of the Gurlitt Gallery.

Lovis Corinth - Selbstbildnis - Ausstellung Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

Alfred Kubin - Die Erde zittert - Ausstellung Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

Max Pechstein - Bildnis Karl Schmidt Rottluff - Ausstellung Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

This was and is common practice. After all, once an artist has been officially included in a collection, this naturally increases their market value. So it's a win-win situation for everyone involved: the artist, the gallery owner and the collecting institution.

Fast forward to 1937: in the summer, as part of the National Socialist “Degenerate Art” campaign, works of classical modernism were removed from German museums and collections on a large scale as "decaying art", destroyed or sold abroad. The Berlin Kupferstichkabinett was also affected by the confiscations.

However, the curator at the time, Willy Kurth (1881 - 1963), managed to save particularly important collections of important artists by successfully exchanging them for less important works and hiding them in other areas of the collection behind the back of his director, who was cooperative with the National Socialists. He knew what he was risking, as his commitment to modernism was well known to his superiors.

The exhibition shows around 95 works that Willy Kurth bravely saved from loss in the form of individual prints and portfolios.

Many of the works confiscated as "degenerate" were taken to Niederschönhausen Palace in Berlin-Pankow, which had been converted into a central depot, where four officially appointed art dealers soon took care of their realisation. Among them was my grandfather's cousin, Hildebrandt Gurlitt. And Wolfgang Gurlitt also had access to this huge art treasure - at least initially. But that's another story ...

If you are in Berlin at the moment, you should not miss the exhibition “Die gerettete Moderne - Masterpieces from Kirchner to Picasso”, which can be seen at the Kupferstichkabinett on Matthäikirchplatz in Berlin until April 21, 2024.

If you are also interested in the story of Willy Kurth and his rescue, check out this blog post: Willy Kurth

(1) Jules Laforgue, „Berlin – Der Hof und die Stadt, 1887“, Insel-Bücherei Nr. 943, S. 98 – 99. I am particularly pleased that I came across this quote, because once again I have discovered a cross-connection that makes me happy. Jules Laforgue, actually a poet, was secretary to Charles Ephrussi, an important art collector and critic, in Paris. Anyone who has read Edmund de Waal's book “The Hare with Amber Eyes” will recognize this name. For those who have not yet read it, it is highly recommended!

Alexandra Cedrino, historical novels, German author, contemporary literature, literature and art, art history, German history, art dealer family, art trade, erotic art, writer, Die Galerie am Potsdamer Platz, The Gallery at Potsdamer Platz, Gallery Trilogy, Zeitenwende am Potsdamer Platz, Shadows over Potsdamer Platz, Wiedersehen am Potsdamer Platz, Return to Potsdamer Platz, The Passion of Searching and Finding, The Journey of Pictures, historical book series, historical crime novels, historical family stories, Italian translation, Berlin, Potsdamer Platz, 1930s Berlin, National Socialism, Nazi art theft, Salzkammergut, Bad Aussee, Alt-Aussee, Austria, post-war period, Central Art Collecting Point, art scene, looted art, art politics, German art history, post-war Berlin, historical villas Berlin, art collections, Wolfgang Gurlitt, Gurlitt family, art collector, publisher, historical figures, family history, artistic networks, inspiration from family history, exhibition catalog, Hirmer Verlag, Lentos Art Museum Linz, essays and articles, book publications, historical essays, reviews, literary criticism, interviews, literary awards, book fairs, HarperCollins Germany, Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024, Führermuseum, art exhibitions, readings, literary events, book presentations, art history lectures, historical conferences, historical narratives, literary suspense, cultural diversity, artistic freedom, erotic private prints, publishing, art and culture, cultural heritage, art market, Nazi-era art, art historical research, cultural political topics, Wolfgang Gurlitt biography, Wolfgang Gurlitt art dealer, Wolfgang Gurlitt art collector, Wolfgang Gurlitt publisher, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the Nazi era, Wolfgang Gurlitt exhibition, Wolfgang Gurlitt family history, Wolfgang Gurlitt art, Wolfgang Gurlitt estate, Wolfgang Gurlitt and Hildebrand Gurlitt, Wolfgang Gurlitt and National Socialism, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the art trade, Wolfgang Gurlitt art relocation, Wolfgang Gurlitt and the Salzkammergut art depots, photographer, art dealer, German-Irish, Nazis, family, love, art collection.